Published online May 2023

Contents

1 Introduction

1.1 Overview

1.1.1 The issues facing our urban areas such as housing growth and urban repair are complex and sophisticated and therefore require innovative responsive solutions by all those involved within the regeneration and development process. Masterplans can play an important role in helping to shape our urban environment and adopting a masterplanning approach for new major development offers a strategy to deal with many of the complex issues often associated with larger applications.

1.1.2 In its simplest form, a masterplanning approach assists the council by outlining a comprehensive plan of action for development across larger and more complex sites and with agreed parameters influencing building design. The parameters as set out in the masterplan can influence the overall form, scale, massing, height, plot and material of a development. It should be a positive and engaging process that is both responsive and proactive and seeks to establish principles of placemaking from the outset outlining how a place will change physically, economically and socially and who will manage and deliver this process of change.

1.1.3 With this in mind setting out a masterplanning approach for new major developments should outline a comprehensive plan of how an area can potentially be developed in accordance with the aspirations set out within the Local Development Plan addressing areas such as:

- How consideration has been given to wider site adjacencies.

- How the design principles advocated can contribute to successful places.

- The quality of buildings and associated spaces proposed.

- How these are connected to create unique and memorable places.

- How they respond and adapt to surrounding natural and historic environment.

- How they promote sustainable principles.

- How the process engages with local people in a meaningful way.

1.1.4 Masterplans will be required for applications that are defined as ‘Major development’ applications as outlined within Regulation 2 of the Planning (Development Management) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2015.

1.2 Purpose of guidance

1.2.1 This Supplementary Planning Guidance (SPG) provides advice and guidance specific to placemaking and urban design. It applies to the Belfast City Council area and is intended to be a point of reference for:

- Planning officers in assessing and making recommendations on planning applications.

- Councillors who make decisions on planning applications.

- Applicants and their multidisciplinary design teams (urban designers, architects, landscape architects, developers and planning consultants), in preparation of applications.

- Communities and their local representatives.

- Other interested stakeholders within the planning process.

1.2.2 This SPG represents non-statutory planning guidance that supports, clarifies and/or illustrates by example, policies contained within the current planning policy framework, including development plans and regional planning guidance. The information set out in this SPG should therefore be read in conjunction with the existing planning policy framework, most notably the Strategic Planning Policy Statement (SPPS) for Northern Ireland and the Belfast Local Development Plan Strategy.

1.2.3 This SPG should also be read in conjunction with the Plan Strategy and full suite of Council SPGs, in particular Placemaking and Urban Design SPG, Tall Buildings SPG and Residential Design SPG.

2 Policy Context

2.1 Regional planning policy and guidance

Regional Development Strategy (RDS) 2035

2.1.1 The RDS provides regional guidance under the three sustainable development themes of economy, society and environment in relation to design issues. Policy RG7 supports urban and rural renaissance by recognising the unique qualities of our cities towns and villages to attract investment and activity ensuring quality urban areas are improved, maintained and enhanced with adequate provision of green infrastructure and the design and management of public realm.

Strategic Planning Policy Statement (SPPS) for Northern Ireland (2015)

2.1.2 The SPPS outlines that good design can change lives, communities and neighbourhoods for the better. It also outlines that new buildings and their surroundings have a significant effect on the character and quality of a place, defining public spaces, streets and vistas and creating the context for future development. Emphasis is placed on placemaking as a people-centred approach to the planning, design and stewardship of new developments and public spaces that seeks to enhance the unique qualities of a place, how these develop over time and what they will be like in the future.

2.1.3 The SPPS states that the key to successful placemaking is identifying the assets of a particular place as well as developing a vision for its future potential. This includes the relationship between different buildings, the relationship between buildings and spaces; the nature and quality of the public domain itself, the relationship of one part of a village, town or city with other parts and the patterns of movement and activity that are thereby established.

2.2 Local planning policy

Plan Strategy

2.2.1 The Local Development Plan (LDP) Plan Strategy provides the strategic policy framework for the plan area as a whole across a range of thematic areas. It sets out the vision for Belfast as well as the objectives and strategic policies required to deliver that vision, based on a suite of topic-based operational policies, including those relating to placemaking and urban design.

2.2.2 The SPPS states that poor design should be rejected, particularly proposals that are inappropriate to their context, including schemes that are clearly out of scale, or incompatible with their surroundings. To this end, the councils placemaking and urban design SPG supports the SPPS in resisting poor design, particularly development which is of poor design quality.

Local Policies Plan

2.2.3 Once adopted, the Local Policies Plan (LPP) will set out site-specific proposals in relation to the development and use of land in Belfast. It will contain local policies, including site-specific proposals, designations and land use zonings required to deliver the councils vision, objectives and strategic policies, as set out in the Plan Strategy. This guidance aims to highlight ways in which these attributes can contribute to positive placemaking within the planning system.

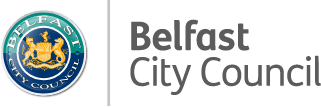

Image 1: Local Development Plan Policy Context Diagram illustrates how Policy DES2 Masterplanning approach for major development sits below overarching Strategic Policies, in particular SP5 Positive Placemaking, and its consideration alongside a range of accompanying topic based polices within the ‘Shaping a liveable place’ theme as well as other relevant thematic polices.

3 Masterplanning approach for major development

3.1 Holistic approach

Policy DES2: Masterplanning approach for major development

Planning permission will be granted for major development where it accords with the following masterplanning principles:

(a) Adopt a holistic approach to site assembly, layout and design that is mindful of adjacent sites, where suitable for redevelopment, while avoiding prejudice to future development potential and or quality where development is of a significant scale and prominence.

3.1.1 How well a place is understood will be one of the most important aspects of how successful a scheme will be. Applicants will need to undertake and communicate this understanding of a sites context clearly and simply, demonstrating that the design has undergone a thorough site analysis and contextual review with consideration given in the initial stages to a holistic approach to site assembly. This should not be limited to current context, but also include and analysis of the historic context for example former functions and uses of the site through time and how this has influenced the place as we know it today.

3.1.2 Prior to setting out an overarching vision and design principles, consideration should be given in the first instance to the unique characteristics of the site including the availability of any adjacent plots of land that may or may not lie outside the applicant’s ownership. Considering such plots from the outset can result in a more meaningful and robust site analysis and in turn a more legible masterplan particularly when in doing so helps to regularise restrictive or challenging boundaries. This approach is not only more sustainable but can also help to futureproof adjacent sites and avoid prejudicing their development in future.

3.1.3 Applicants are therefore encouraged, where appropriate, to consult adjacent landowners early on to ascertain the benefits that a joined up approach may bring to the masterplanning process and the wider aspirations of the area. While this can sometimes prove challenging, efforts should be made to demonstrate that meaningful engagement has taken place with adjacent landowners.

3.1.4 It is important that when adopting a masterplanning approach for major developments that the applicant considers the masterplan as a dynamic document that incorporates a degree of flexibility and does not set rigid or overly prescriptive design criteria for the future development and design of the proposal. The scope of design criteria can range from a ‘Design Statement’ which outlines broad design parameters that should be applied across the site, to a more prescriptive ‘Design Code’ that sets out rules or code for individual plots within the scheme (see paragraphs 3.1.10 – 3.1.16). In either case, the aim is to establish the context and aspirations for the site that can be adapted over time through a phased approached with a degree of flexibility. Clearly identifiable phases within a scheme can help accommodate changing project conditions, demands and expectations. It is important that the initial vision is not lost or diluted through subsequent design iterations.

Site assembly

3.1.5 Successful places strike a harmonious balance between connections, spaces and buildings. Plot sizes, the shapes of buildings including their scale height and massing are factors to be considered in establishing this balance, however it cannot be one single determining factor. From an urban design viewpoint, open spaces and areas surrounding buildings and plots are equally important if not more important than the as the buildings themselves and need to be considered from the outset with regards to their intended use. The same can be said if too much focus is placed on open space provision which can potentially lead to rigid plot widths and can overly restrict architects when designing buildings.

3.1.6 By utilising a masterplanning approach several varying proposals can be tested. Such tests may include;

- Where developments occur in areas where archaeological remains of the city’s historic environments are likely to be encountered, masterplans should consider how this work, as it progresses can be promoted to surrounding communities, allowing engagement with their past and achieving public benefit.

- Does the plot make sense in relation to likely sizes, shapes and uses of buildings? For example, some plots may be too big for a single building or too small to provide sufficient amenity space. This should be assessed by drawings at an appropriate scale, in section and plan. The appropriate block size may depend on the intended use (if known) which can determine the likely scale of the building, need for amenity space and associated service provision;

- Do the proposed block sizes, width and form relate to the historic context and grain of the site, so that new development is responsive to the character of an area.

- In cases where the intended use is not yet established it is important that the blocks and plots contain a degree of flexibility so as not to overly restrict their future use;

- What levels of permeability are provided for pedestrians, cyclists, public transport and other vehicles? Are pedestrians and cyclists allotted adequate priority throughout the site?;

- How will the built form affect microclimates? Can site conditions be utilised to increase energy efficiencies?

3.1.7 In responding to these queries, the level of detail provided should allow for greater certainty and provide the basis for a structured masterplan approach which demonstrates;

- How streets, squares and public open spaces are connected.

- The hierarchy of building scale, height and massing.

- The relationship between buildings and spaces, clearly defining public and private areas and any impact on amenity.

- The range of uses and intended activities.

- The levels of movement through the site including desire lines and wider cycling and walking networks focusing on pedestrians and active travel with adequate provision made for public transport, vehicular movement and service access.

- All service provision requirements for utilities, including water, gas, waste etc.

- A greater understanding of how the proposal will connect and integrate with its wider context including surrounding communities and natural environment.

3.1.8 With regards to how the proposal connects and integrates with its wider context, cognisance should be given to any existing published strategies that may have a bearing on the site. These may include masterplans and frameworks produced by the council and/or statutory agencies such as the Belfast City Centre Regeneration and Investment Strategy, Inner North West Masterplan, East Bank Development Strategy, Belfast Entries Project and the Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan to ensure compatibility and alignment with any agreed visions, aims and objectives. Consideration should also be given to the transport/road network, any relevant Transport Assessment and DfI's Strategic Transport Master Plans.

3.1.9 Applicants are encouraged to demonstrate the masterplanning approach process using 3D model imagery, and where appropriate utilise VUCITY.

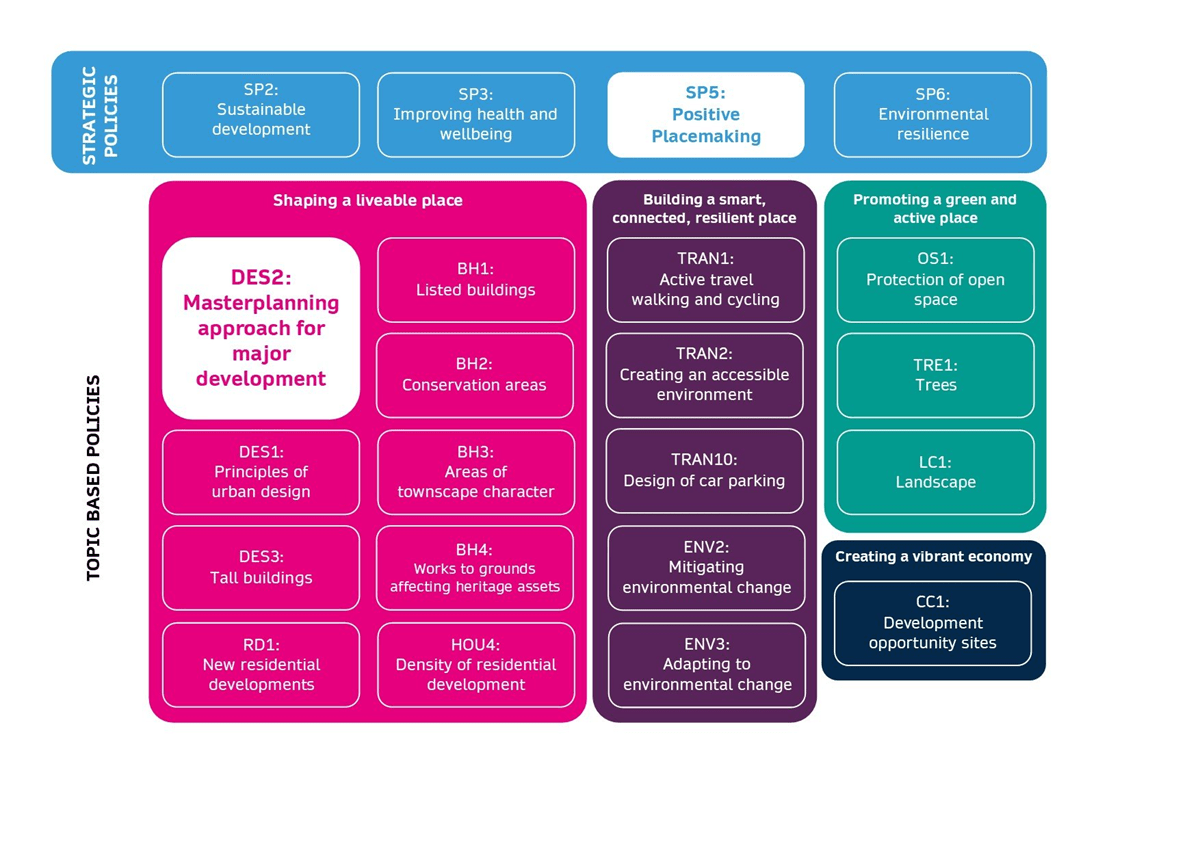

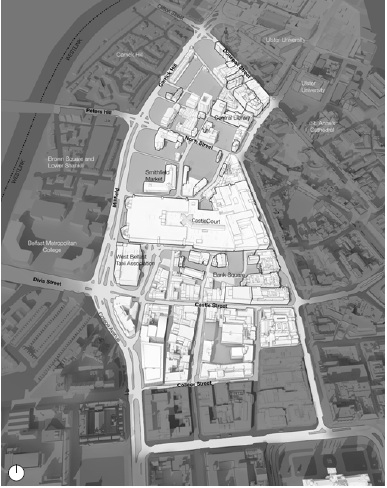

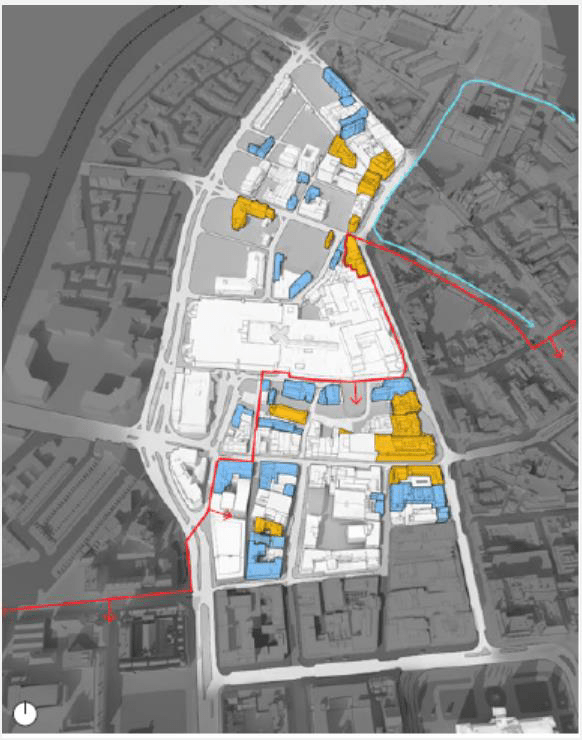

Images 2 to 5: Inner North West (INW) Action Plan Area (contextual analysis)

The images below illustrate some of the contextual analysis undertaken during a masterplanning approach for future development within the north west area of the city centre. Analysis included examining historical mapping, identifying heritage assets and understanding the extent of underutilised sites and those sites under public ownership.

Yellow area: Listed buildings

Blue area: Buildings of local significance

Red line: City Centre Conservation Area

Blue line: Cathedral Conservation Area

Blue area: Underutilised sites

Yellow area: Surface car parking

Green area: Land under public ownership

Red line: City Centre Conservation Area

Blue line: Cathedral Conservation Area

Design statements

3.1.10 Design Statements can be an effective tool in prescribing broad design parameters for small to medium sized sites to illustrate the thought processes underpinning the design. They can be used as a means of explaining the design concept for the proposal, beginning with the basic preposition for the site and illustrating by way of clear and coherent masterplanning principles how the scheme responds to policy contained within the Local Development Plan.

3.1.11 The Design Statement therefore establishes the basis for a structured and reasoned approach to the design grounded in analysis conclusions drawn from local context. It should be written in a way that avoids jargon to ensure that it can be easily interpreted and understood by a wide audience of readers including members of the public, community representatives, elected representatives and council officers.

Design codes

3.1.12 Once masterplanning principles are formulated, further detail can be set out in the form of Design Code depending on the size and complexities associated with the site. The level of detail provided can be broad or provided on a plot by plot basis, however it should underpin the key masterplanning/urban design principles that are being sought as well as reflecting the overall vision for the area. Applicants are advised to seek clarity with the council at an early stage, preferably during PAD, as to whether their site would require a 'Design Statement' or in the case of larger more complex sites a 'Design Code'.

3.1.13 Design Codes are useful tools within the application process, particularly for larger more complex sites and ones with longer term implementation strategies that could see the client/developer change throughout the time period of the proposal. The Design Code sets out rules or code for the design of new development across the full extent of the scheme and represents an illustrative interpretation of the broader masterplanning/urban design principles illustrating the intent for development plots contained within the masterplan. They are a more detailed expression of the illustrative Masterplan and for council represents a valuable tool in retaining quality within a scheme and as a key point of reference in determining future reserved matters applications as the masterplan is brought forward.

3.1.14 Information within the Design Code should provide enough detail to secure the intent of the illustrative scheme while affording a degree of flexibility to future designers in considering what is deemed appropriate. Information would typically relate to proposed use, layout, scale, open space, plant/servicing, articulation of elevations, materials and where appropriate the relationship between buildings and any new extension. It should also include a palette for materials, public realm, street furniture and space standards for residential uses, yet allow a degree of flexibility for architectural expression and innovation.

3.1.15 This provides the council with a strong, evidence-based framework document to help guide and inform the roll-out of development across the masterplan, irrespective of which developer/applicant comes forward to realise particular sites.

3.1.16 Particular care will be necessary in preparing layout proposals on sloping sites in order to minimise the impact of differences in level between adjoining properties, existing or proposed. The use of prominent retaining walls within and at the margins of sloping sites will be unacceptable. Where changes in ground level between buildings are unavoidable the Council will generally expect these to be accommodated by the use of planted banks. It may be appropriate to consider the use of bespoke/specialist house designs which respect topography, such as split level dwellings. In all cases it will need to be demonstrated that the proposals will avoid significant overshadowing, overlooking and loss of privacy.

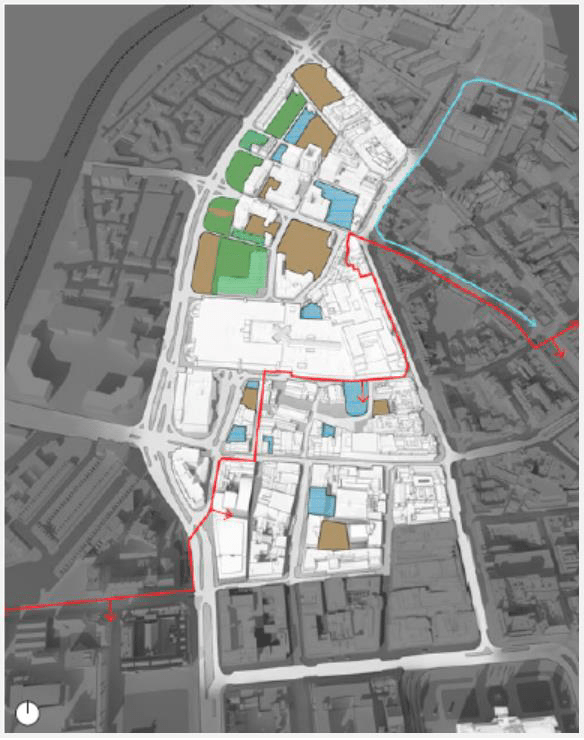

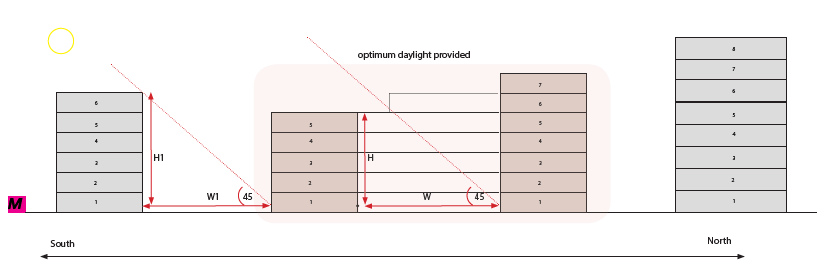

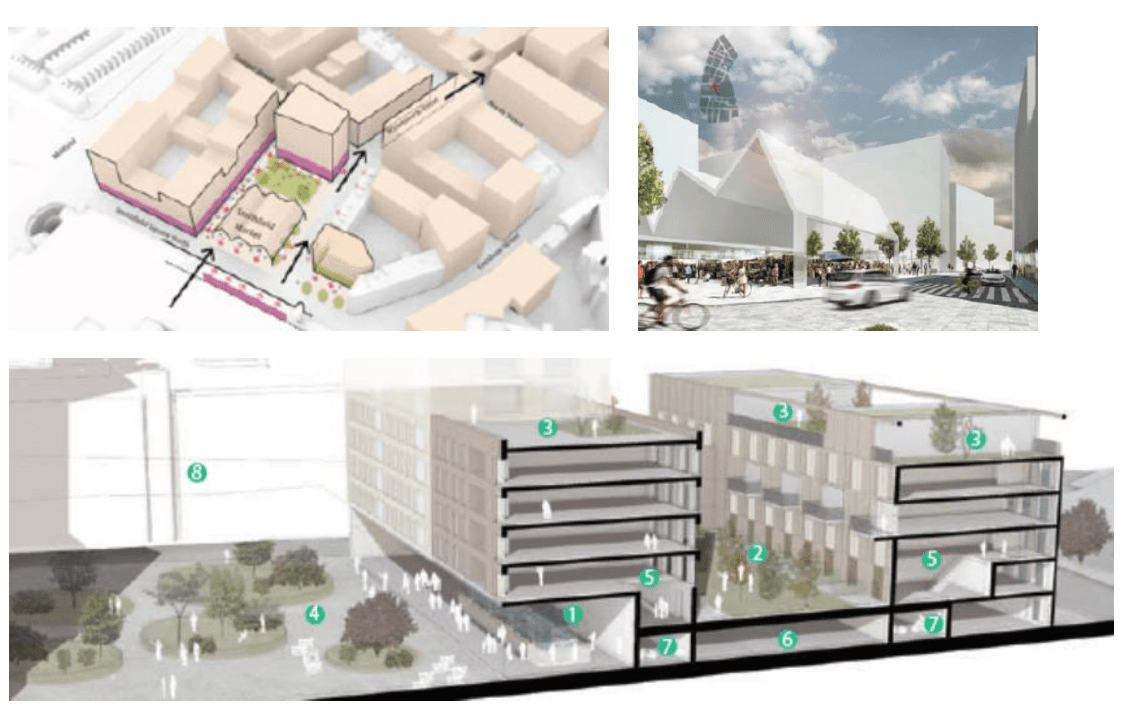

Images 7 to 9: Inner North West (INW) Action Plan Area. The INW Masterplan proposes a reimagined Smithfield Market as a new city square defined by development with active frontages. Cross-section diagrams help to illustrate one way of designing new homes above active ground floors with raised internal communal courtyards.

- Market

- Landscaped podium

- Private roof terrace

- Landscaped public realm

- Duplex

- Resident car parking

- Bike store

- Castle Court

3.2 Urban repair and connectivity

Policy DES2: Masterplanning approach for major development

Planning permission will be granted for major development where it accords with the following masterplanning principles:

(b) Promote opportunities for urban repair and greater connectivity to neighbouring areas by minimising or mitigating physical barriers that create undue effort or separation, informed by feedback from existing communities.

3.2.1 Areas of the city that have experienced post-industrial decline or have suffered from a lack of investment can present opportunities for new regeneration projects. Where the opportunity exists, new development proposals should seek to repair and reknit the urban environment while creating new connections that provide welcoming, well designed, and sustainable environments. Adopting a masterplanning approach to such areas should look beyond the red lines of the site and consider the wider impact of new development. Major development should seek to realise opportunities to enhance the urban context, by way of linking or creating green spaces, cycle lanes, leafy shaded places for people to meet, rest, talk, play, prioritising the pedestrian and cyclist.

3.2.2 Urban repair can also help alleviate those sections of the city which have suffered from poor transport infrastructure and a legacy of unsympathetic development which has resulted in physical barriers that restrict movement and create undue effort or separation. Establishing legible and well-connected layouts is an essential design consideration. It is imperative that new interventions enhance connectivity not only within the site but beyond to neighbouring areas.

3.2.3 Balancing the needs of access and movement while creating a high-quality development requires innovation and creativity. It is important that active modes of transport are considered from the outset to avoid the dominance of vehicular movement that has impacted many parts of our city.

3.2.4 This is of particular importance when developing brownfield sites within the city which may have been left underdeveloped due to the lack of connectivity. Existing and historic context and levels of connectivity should provide the starting point from which to formulate new patterns of development. Research to understand what the previous function and use of the brownfield site was, may help to develop and inform desire lines and linkages.

3.2.5 Poor connectivity will limit the success of the masterplan irrespective of the quality of development proposed and as such development proposals that fail to address these issues will not be considered acceptable. Greenways and green routes are one approach that could be widely implemented across the city. safeguarding appropriate land within masterplans that could futureproof the development of green connections.

3.2.6 Infrastructure, utility connections and site conditions should also be considered at an early stage as these can pose constraints that can be difficult to mitigate further within the development and design process.

Pedestrian bridge connecting the east of the city to the city centre.

Addressing physical barriers

3.2.7 One of the main contributors which constrains permeability and movement across the city is the legacy of strategic road infrastructure and the degree of disconnect that this has caused at a local level, an issue which is readily apparent along the northern edge of the city centre. The extent of this issue is such that the term ‘shatterzone’ has been coined to describe the damage caused to the urban environment by interventions such as motorways and feeder routes which were carved through some of the city’s more historic and tightly knitted urban areas to cater for an increasingly motorised society.

3.2.8 A contentious issue and one very unique to Belfast is the profound and lasting impact that the Troubles have had on our urban environment in relation to physical barriers. The most recognisable of these include ‘Peace Walls’ and interfaces which define boundaries along community lines. Any proposal to remove structures of significance relating to the Troubles should be given appropriate consideration in terms of their heritage impact and their impact they have had on our society and urban form. Such structures, though not designated can have heritage significance and should be accompanied by a Heritage Impact Assessment.

3.2.9 On a more localised level challenges also exist in the form of poorly connected residential areas, where points of access were restricted and the use of cul-de-sacs widespread in order to address concerns of security forces. These challenges also extend to those less obvious barriers to movement such as shopping centres, industrial estates and swathes of ‘left over’ open space, all of which have been used in various guises to reinforce and define boundaries between communities.

3.2.10 In the layout of new masterplans, every opportunity should be taken to positively effect change by alleviating such physical barriers. Where appropriate the opportunity should be taken to remove or redesign where such elements are considered redundant or superfluous. Where structures may have a local or historic significance, applications should outline how they can be represented or changed to retain an appreciation of the history of the site, while improving connectivity. Here priority should be allotted to pedestrian and cycle movements with the aim of re-stitching fragmented areas of the city and promote walkable neighbourhoods. Issues such as hierarchy of routes, street design, public realm, public transport network, service provision, vehicle access points and parking need to be appropriately balanced and should be given due consideration at the earliest stage of the masterplan development.

3.2.11 Utilising a masterplanning approach to site assembly also increases the potential to integrate vehicular movement within the overall design. However these issues should not be considered technical challenges that fall solely within the remit of road/transport engineers, but should instead be considered collaboratively by the wider masterplanning team and affected communities with good placemaking principles at the forefront.

3.2.12 The consultation process for major development is critical in obtaining an understanding of the main areas of concern facing communities, but also is an opportunity to gain community support for new proposals. Establishing these connections with the community early on within the design process and taking into account the cumulative impact of the proposal should be considered. This will be evident long after the development is completed.

Case Study 1: Connswater Community Greenway

A 9km linear park through east Belfast following the course of the Connswater, Knock and Loop Rivers, connecting open and green spaces. The multipurpose greenway not only provides an attractive, safe and accessible parkland for leisure, recreation, community events and activities but also includes an £11 million flood alleviation scheme that has helped reduced flooding to 1700 properties. Eastside partnership along with BCC delivered the scheme that underwent an extensive public consultation and engagement process.

3.3 Energy efficiencies

Policy DES2: Masterplanning approach for major development

Planning permission will be granted for major development where it accords with the following masterplanning principles:

(c) Maximise solutions to deliver energy efficiencies that seek to achieve BREEAM ‘excellent’ or comparable standard.

3.3.1 There is greater potential for larger scale development sites to positively contribute to combatting issues of climate change. The incorporation of energy efficient technologies and passive design approaches across larger sites can have a significant impact when planned at this scale. For example, this is evident within proposals that implement district heating schemes which are considered viable when they serve multiple buildings with differing heating requirements.

3.3.2 It is also important that proposals consider the adaptive reuse of existing buildings where the opportunity to do so exists. Existing buildings will contain embodied energy that will mostly be wasted if the building is demolished, along with the energy required to dispose of building materials and rebuild. The conversion of an existing building may therefore be more acceptable than replacement and in many cases such buildings will already be located in accessible areas possibly close to transport and key facilities.

3.3.3 In order for such adaptive measures to be assessed to create sustainable developments the policy criteria sets out an aspiration for developments to achieve BREEAM excellent. BREEAM certificates apply international standards during the planning and design stages of development and this method offers a holistic approach with a number of targets to assist decision makers. The assessment carried out goes beyond legislative minimum requirements and can provide decision makers with a greater degree of certainty when it comes to achieving energy efficient and sustainable development.

3.3.4 The council encourages the responsible reuse, reappropriation and upgrade of existing buildings with any new interventions being sympathetic to the buildings age, character and construction. Cases may exist where it would be deemed appropriate to demolish the existing building, however these should be treated as the exception and not the norm and supplemented by appropriate justification.

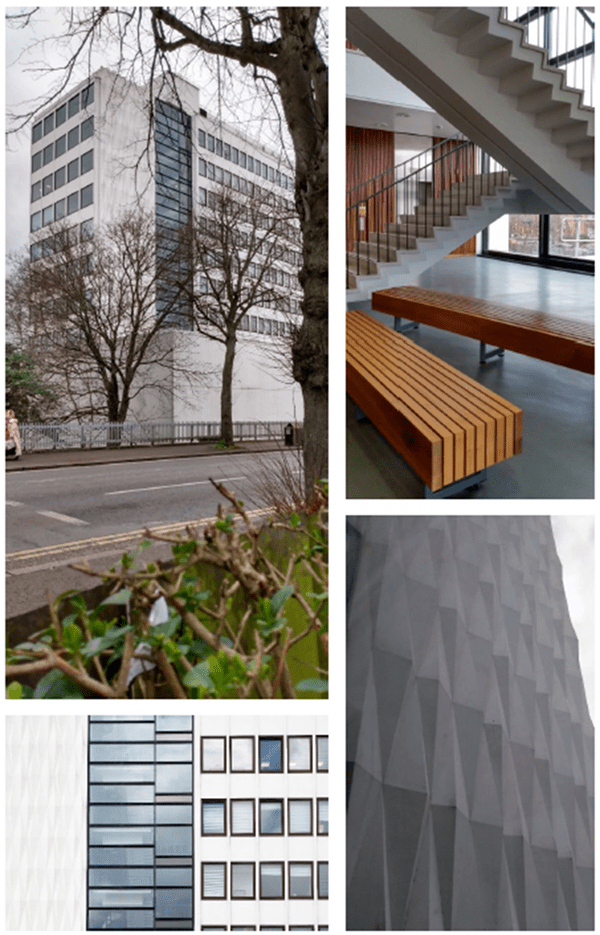

Case Study 2: Ashby Building, QUB Belfast

Originally built in 1964 to designs by Cruickshank & Seward, refurbishment of the Ashby building began in 2006. Energy efficiencies and environmental strategies are being implemented as reflected by the targeted Very Good BREEAM rating.

3.4 Higher densities

Policy DES2: Masterplanning approach for major development

Planning permission will be granted for major development where it accords with the following masterplanning principles:

(d) Promote higher density residential and mixed use development along city corridors and at gateway locations.

3.4.1 Higher densities can be appropriate for compact city living where more sustainable forms of development would be preferred by increasing massing along city corridors, around regional and local centres, parks and riverfront locations and where sites are easily accessible by public transport. Even the most energy efficient developments will not be considered sustainable by most measures if they can only be accessed by the private car. Increasing residential densities near public transport hubs and along city corridors can significantly reduce reliance on the car and reduce the demand for lower density developments. Achieving efficiencies of land use should be considered in tandem with the objectives of creating well designed places that are pleasant to live in.

3.4.2 What is sometimes overlooked is that a large proportion of our much admired Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian terraces resulted in higher densities that often far exceed density limits advocated within existing development plans and dispels perceptions that often conflate high densities with high rise. As density is only a measure, the challenge is to avoid a ‘one size fits all’ approach and instead encourage a variety of densities and building types that collectively sustain the local character of an area while contributing to its sense of place.

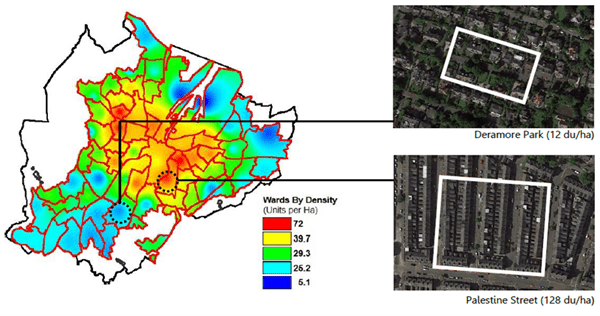

Images 11 to 13: A heat map of densities across Belfast ranging from 12 dwellings per hectare (du/ha) at Deramore Park to Palestine Street in the Holylands where denities of around 128 du/ha are not uncommon. This dispels perceptions which can often conflate high densities with high rise.

Case Study 3: Ross Mill Avenue, Belfast.

A regeneration project providing 165 homes and a new shop. The design was based around the preservation and conversion of a 19th century flax mill and its landmark chimney, and the creation of a new urban block.

3.5 Improving and managing public realm

Policy DES2: Masterplanning approach for major development

Planning permission will be granted for major development where it accords with the following masterplanning principles:

(e) Contribute positively to the improvement of the public realm within, and in the proximity of, the development through the use of high quality materials and street furniture.

(f) Include an appropriate landscape management plan, early in the planning process, as an integral part of the landscape proposal.

3.5.1 Inclusive design is defined as that which meets the needs of all users and in its broadest sense means creating places that can be enjoyed by all. Development proposals should not try and mitigate perceived social problems by turning their back on neighbouring areas. Developments proposing gated access which restricts public access can lead to unsustainable, inward looking communities.

3.5.2 For major developments it is of particular importance that the design and implementation of public realm is of high quality, clearly defined with sufficient measures in place to ensure an adequate degree of passive surveillance and overlooking in order to prevent crime and maintain public safety. New public spaces should allow for adaptable uses that connect and enhance existing spaces with a palette of materials that complements the character of surrounding buildings. In addition to hard landscaped areas, the opportunity should be taken within new developments to incorporate usable green spaces to address the shortfall experienced across the city centre.

3.5.3 In cases of hard landscape the design should pick up existing details such as paving materials and sizes of paving units with an integrated approach taken in the design and siting of elements within the public realm such as seating, signage, bins, railings, lighting, public art and cycle storage etc. to ensure that these elements are carefully coordinated and align with wider public realm works.

3.5.4 The desire to create interesting, active and diverse public realm that contributes socially and environmentally to the city can sometimes cause conflicts with the desire to minimise maintenance costs or avoid undue risks. Such issues need to be considered at the initial design stage and may include the implementation of a landscape maintenance plan. In such cases, the quality of the landscape design should be beneficial to occupiers and can in many cases improve the value of the scheme which may offset any future maintenance costs.

3.5.5 Designers should ensure that landscaping proposals are as far as feasibly possible low maintenance, whereby they do not require frequent pruning, weeding or cleaning. This may impact the selection of plants species, surface materials and street furniture. It is also important that adequate safety precautions are considered for example where a scheme seeks to incorporate blue infrastructure and suds. Here the design should aim to keep pedestrian movement within designated paths orientating people away from any perceived risks. In some cases, this can be managed through innovative planting and landscaping. Where possible the use of safety barriers and physical interventions should be avoided as such infrastructure can lead to a cluttered and unwelcoming space.

Images 14 to 17: Public realm

Examples of high quality public realm across the city centre which have resulted in a series of transitional and dwell spaces that include seating, lighting, tree/shrub planting, wayfinding signage and artwork.

3.6 Character and setting of River Lagan

Policy DES2: Masterplanning approach for major development

Planning permission will be granted for major development where it accords with the following masterplanning principles:

(g) Enhance the waterside character and setting of the River Lagan, including the improvement of existing and provision of new access points and new cross river connections where appropriate.

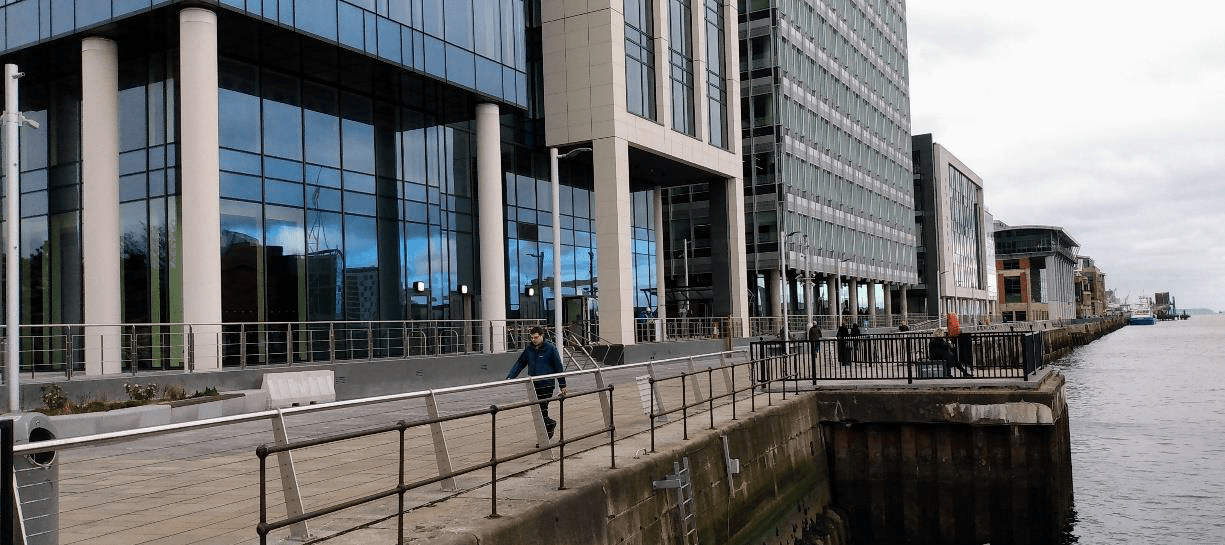

3.6.1 The River Lagan has in more recent years become an amenity corridor within the city centre context and beyond, catering for a wide range of users including walkers, joggers and cyclists as well as an increased use of water-based activities. The potential for river front sections of the city to be regenerated has been witnessed by the recent construction of the mixed use development scheme at City Quays one of the largest strategic investments to be undertaken by Belfast Harbour as well as the aspirations contained in the approved masterplan at Sirocco.

3.6.2 Additional opportunities should be taken to enhance the waterside character and setting of the river and strengthen the relationship between it and city centre. Where development is proposed on sites along the river, officers will seek to fully utilise their waterfront locations in the first instance by securing public access along its length in the form of high-quality public realm works. This will provide the basis upon which to reactivate and reanimate the river through appropriate built form and mix of uses and where possible increased water activity for both leisure and transport purposes. Forging strong connections across to the east of the city is also paramount and could be enhanced in future by way of additional footbridges linking strategic points either side of the river.

Image 18: Recent and ongoing construction at City Quays has resulted in a continuation of high quality public realm along the river.

3.7 City landmarks and public art

Policy DES2: Masterplanning approach for major development

Planning permission will be granted for major development where it accords with the following masterplanning principles:

(h) References unique parts of the city through the realisation of key landmarks within prominent or gateway locations.

(i) Seek to include where appropriate the provision of public art.

3.7.1 The urban planner and theorist Kevin Lynch’s most renowned work ‘The Image of the City’ (1960) identified a range of physical elements which the author suggests formed the building blocks of place with these elements being path, edge, district, node and landmark. The key premise of the author’s argument was that people in urban environments orientate themselves by way of mental mapping which affects the way we comprehend (legibility) and allot meaning of place (imageability). In this context ‘landmarks’ denoted external reference points of orientation often in the form of an easily identifiable physical object within the urban landscape.

3.7.2 While sensitivity is required in relation to their location and potential impact, landmarks can have a role to play as key points of reference that contribute to the legibility of the city and orientation. In terms of urban interventions these elements represent the prominent visual features of the city and can take the form of buildings which are unique and memorable. While landmarks can be quite large and identifiable at great distances, in the Belfast context these were historically of a more domestic scale taking the form of cathedrals, churches and civic buildings such as halls, schools, libraries and clock towers that struck a modest degree of contrast against the low level city backdrop. New buildings or structures do not however have to be tall to provide a landmark within the city. New development which is innovative in terms of high quality design and materials, sympathetic and responsive to its context can also provide reference points to aid orientation.

3.7.3 In addition to buildings, reference points within the city can also take the form of easily recognisable and localised signals that help to trigger spatial awareness in wayfinding and include interventions such as public art. Rooted historically in public monuments and commemorative memorials, public art has developed and responded to the changing socio-urban environment. They can have a role to play in establishing visual landmarks around the city in a way that adds depth and richness to the public realm while reinforcing local and cultural identity. Public art can also help determine the character of a place and where embraced see their status elevated as symbols of the city.

3.8 Retention of existing trees

Policy DES2: Masterplanning approach for major development

Planning permission will be granted for major development where it accords with the following masterplanning principles:

(j) Seek the retention of existing trees within and around the site and make adequate provision to allow them to mature while ensuring the continuance of tree cover through new tree planting.

3.8.1 Trees and landscape also play a significant role and add value to the quality of public realm. They should be carefully specified and sited to allow for adequate soil depths, light, water and air to ensure healthy growth. Due cognisance should also be given to the retention of existing trees where possible early in the masterplanning process alongside the provision of new tree planting, particularly in cases where trees are removed to facilitate development

3.8.2 Trees in Conservation Areas will be required to be retained unless the application includes an appropriate tree survey and justification for their loss or replacement. This issue is addressed in further detail within a separate Trees SPG.

Images 19 and 20: Where tree retention or planting is proposed in conjunction with nearby construction, a key site component should be to achieve a harmonious relationship between trees and structures that can be sustained in the long term.

Image Credits

Images contained within this document are subject to copyright restrictions and cannot be reproduced without the owners permission.

Image copyrights are owned by Belfast City Council, except where stated below;

| Image | Photo credit |

|---|---|

| Sirocco Design Code | Henning Larsen Architects |

| QUB Ashby Building, Belfast | Belfast City Council |

| Ross Mill, Belfast | Chris Hill Photographic |